Express Tribune 24 August 2013

We miss many things when we’re living away from home - mangoes, bun kebabs, paan, the dust, the loadshedding. Okay, okay, just kidding! We miss some of these things, but we manage without them, one way or another.

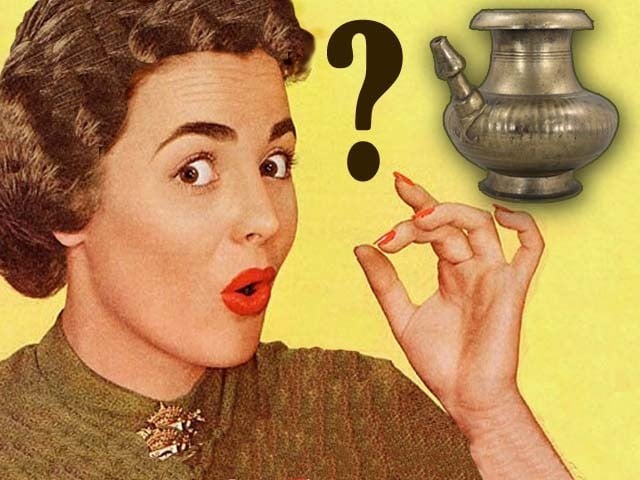

There is one thing you cannot do without, though, and that’s the lota. It is such an integral item of sub-continental and Muslim culture, that even a short term visitor such as the famous American designer Charles Eames couldn’t help but notice it most particularly when he visited India in 1958. He had this to say about it:

“Of all the objects we have seen and admired during our visit to India, the lota, that simple vessel of everyday use, stands out as perhaps the greatest, the most beautiful.”

There you go. Beautiful? Yes, he was talking about the brass lota that the village women clean and polish with tamarind and ash each day, turning the ‘brass into gold’. They are beautiful… and very heavy.

Most people flying out struggle with weight restrictions, so carrying a heavy brass lota in your luggage is an extravagance when there are achaars (pickles), chilli chips and bottles ofMushroob-e-Mashriq sherbet fighting for space in a suitcase. The ubiquitous, elemental, and exceedingly essential lota loses out in the process. You will not see brass lotas much outside Pakistan. Instead, you’ll see ugly plastic ones which replaced the bronze ones in Pakistan a while ago in any case.

So what do you do once you’ve reached your particular pardes and you have no lota in the new house? You reach for the nearest milk bottle, of course.

You’ll find all sorts of milk bottles in people’s bathrooms out there – full cream, low fat, skim, soya, chocolate, vanilla, or my favourite, strawberry. People are strangely coy about them.

“Why’s there always a milk bottle in your bathroom?” visitors have asked – always American.

They’re refreshingly forthright.

In England I caught a native looking bemusedly at my strawberry soya milk bottle (organic) before she shut the door to the powder room, and I waited with an array of answers provided by errant nephews (one of whom claimed to possess a folding lota that fit in his wallet, but it turned out to be only a zip lock bag) for just this purpose.

The answers included:

1) I use it all the time to irrigate my nose. I have a deviated septum.

2) I prefer strawberry soya, so I removed the chocolate you saw when you were last here; sorry.

3) Would you prefer the chocolate? I can put that back if you like.

4) It’s a Pakistani superstition.

5) In Pakistan we like to keep our cows in the bathroom, but we can’t do that here, and the milk bottle reminds the kids of that tradition.

Or simply:

6) Which milk bottle? (That one really freaks them out for a while)

Sadly, for one reason or the other, most of those responses were not used – firstly because the Americans are honest enough to ask without being oblique so you are not tempted to match delicacy with wit, and secondly, because the Brits would rather die before they ask any such question. They’d pick their way through 10 milk bottles in a single bathroom and pretend it was a normal feature of every bathroom decor. In fact, they would claim that “it was Aunt Doris’ favourite bathroom accessory too, wasn’t it, Anthea?”

Oh, why the fuss! Bring the lotas out of the closet. Let Ikea carry dismantle-able ones in their standard flat colours, and back here in Pakistan, how about Haji Karim Baksh carrying a line of lota gifts for relatives in the West?

‘Loin of the Punjab!’ (sic) proclaims a T-shirt in one of the shops in Lahore, alongside a gun-toting portrait of Sultan Rahi. The lotas could carry just that slogan, no Sultan Rahi required at all.